Country of Origin and Customs Planning: Duty Strategies in Extraordinary Times

In both ordinary and extraordinary times, customs planning, a/k/a duty minimization, is a major pre-occupation for importers and their advisers. So, is there a difference in the planning strategies that are explored in ordinary vs. extraordinary times? Yes.

Let’s first define what I mean by these two terms. For me, an ordinary time refers to a period when the environment is settled and sedate. It’s a time of steady and not stampeded review, of change in due course after careful deliberation. An andante pace, if baroque music is to your liking. An extraordinary time is, well, a time when things are not settled, when changes come fast and furious, when being able to proceed with all deliberate speed is a cherished memory only. It is a time that may demand a decision on the spot…and “on the fly.” It is an allegro or even a prestissimo tempo and you feel you are always a note, or two notes, behind.

So, you will know we are in an extraordinary time. And the planning strategies are different. Or, more accurately, while the available planning strategies remain the same, the relative usefulness of one or another will have shifted. This is the time to think about shifting the country of origin of the imported goods.

STATUS QUO ANTE

In the dim past, i.e., prior to January 2025, the importer of goods into the U.S. would be looking at the duty rate for a given article fixed by three columns in the Harmonized Tariff Schedule of the United States (HTSUS). The rates assigned to an article classified in a 10-digit tariff item would vary depending on the county of origin (COO) of the product. Bear in mind the article could be identical and its tariff classification could be exactly the same. The only variable would be the COO of the article.

The normal tariff would be assessed on imports of goods from countries that enjoyed most favored nation (MFN) treatment (also referred to more recently as normal trade relations, NTR). This is in the “General” portion of Column 1. The middle column, designated the “Special” portion of Column 1, was reserved for goods with trade preferences, and free or reduced rates would apply. On the right side, the third column, confusingly named Column 2, was reserved for those countries that are stuck with the 1930 tariff levels. Currently those are Cuba, North Korea, Russia and Belarus.

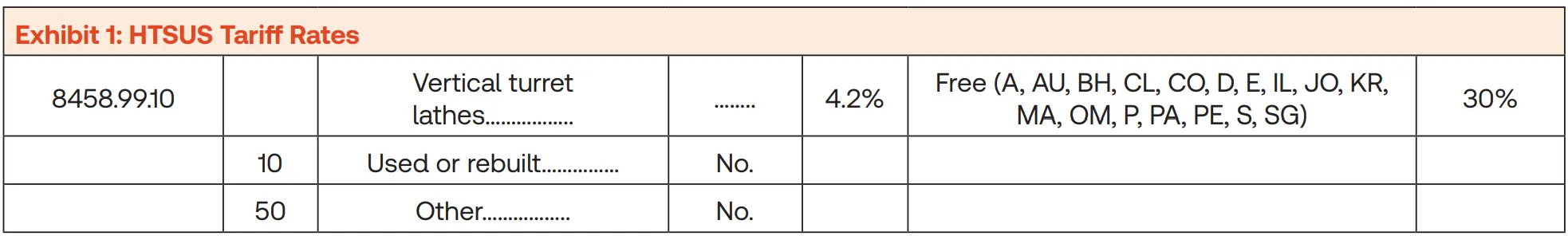

To illustrate this, see Exhibit 1 from the current HTSUS:

You will have grasped immediately that the COO of the imported article has always delivered a major impact on the duty paid by the importer. Apart from the obvious—a Free rate of duty is better than 4.2% and 4.2% is better than 30% – if we go back to the times when textile quotas were in place, those quotas were arranged on a COO basis. The scope of antidumping duty (AD) or countervailing duty (CVD) orders is limited to a product with a specifically identified COO.

To be sure, the COO is one of the three elements that determines the duty, the others being the tariff classification and the customs valuation1 . Prior to the impact of the successive Multilateral Tariff Negotiations rounds under the GATT in lowering the 1930 tariff levels, the differences in Column 1 duty rates were very pronounced and the Customs Court calendar was filled with tariff classification cases. Tariff engineering, designing a product to gain an advantageous tariff classification, has a long pedigree. So, too, with customs valuation, whereby an importer may be able to lower its duty bill by “unbundling” nondutiable charges from the declared price for the goods. The First Sale For Export doctrine is another favored planning strategy.

Under the GATT/WTO trading system, the standard Column 1 duty rate was the same for all trading partners. In this prelapsarian time, this made for a very stable environment.

2018 ONWARDS

The whirlwind of trade measures that has upended the trade community actually touched down in 2018. That is when the Section 232 tariffs of an additional 25% were imposed on steel imports and a 10% additional tariff was imposed on aluminum imports. Even then, there was a COO element, as certain country-specific exclusions were adopted and, in the case of Turkey, an increased retaliatory duty was imposed at one point. In July 2018, the first of the Section 301 additional tariffs lists was announced. That tariff was limited to China only. The excerpt from the HTSUS shows a footnote 1 reference. That will take you to tariff item 9903.88.01, which is the tariff number assigned to List 1 of the Section 301 tariff and its additional 25% duty rate.

With the Section 301 tariffs rolled out on a tariff classification basis, and with limited exclusions also provided on a tariff classification basis, there were some efforts to reclassify imported products. That strategy lost its vitality as the successive Lists were promulgated through List 4A on September 1, 2019, and more products were affected. Most of the limited exclusions also expired and reclassification lost its luster.

As for customs valuation, many importers of Chinese goods sought to renegotiate with their Chinese suppliers or to shift to a first sale footing. But the savings realized were typically not enough to deliver a significant relief. With first sale, for example, assuming a 15% middleman markup, and a combined duty rate of 30% (e.g., if from China, our vertical turret lathe would carry a 4.2% and a 25% duty = 29.2% total duty) the savings would be 15% of the duty owed. Thus, for a $100,000 unit, the duty would be $25,500 instead of $30,000. That is a far cry from 4.2%, but the importer might still seek to apply first sale. After all, 15% savings is still 15% savings and if the price might be renegotiated, the savings might be a bit more.

Most importers staring at such a duty bill, however, realized immediately that a business model based on these costs was not sustainable. What to do? A key consideration was whether the importer might find another supplier outside China or whether the Chinese supplier might shift production to another country. U.S. ownership of the Chinese factory was a complicating factor, of course.

MOVEMENT AWAY FROM CHINA

Thus began the great move away from China. It had already begun years before, because the trade relations with China had been strained for over a decade and some early adopters had moved to that new, non-China production model. The Section 301 tariff rollouts in 2018-2019 accelerated that shift.

For the Chinese companies that could relocate production to other locations, this was an opportunity to retain the business with their U.S. customers. This led to an explosion of production capacity in other Asian countries, principally Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia to name a few2 . But there were some production shifts to other locations closer to the U.S., such as Mexico and the Dominican Republic. Those countries offered the bonus of duty-free access to the U.S. market under the free trade agreements in place.

Of course there were many factories; in fact, most factories remained open in China. And U.S. customers still lined up. That may have been because there were no available alternative sources. But there was undoubtedly a major shift underway.

The shift away from China might be a complete transposition, in that the raw materials, parts or components were all locally sourced in that new country. That scenario was not typical. Instead, the production of the finished product would involve what we might term an “interrupted” process, whereby parts would be produced in China and the modules or components would then be shipped to the third country for final assembly or production in a factory owed by the Chinese company. That final assembly might involve non-China parts.

The goal of this production shift was obvious—avoid a COO designation of China to escape the Section 301 tariffs—and perhaps one of the AD or CVD duties that have been applied to hundreds of Chinese products. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) was aware of this, of course. It was an easy pattern to spot, simply looking at the Census Bureau records of increases in imports from third countries on an HTS basis revealed the tremendous growth in production capacity.

What followed was entirely predictable. From 2018 onwards, CBP sent out thousands of requests to importers for information (CF 28s) on the COO. And prudent importers submitted thousands of ruling requests to CBP on COO questions.

So, the state of play in January 2025 was well-settled. Except for the impact of AD or CVD or Section 232 on specific products, a normal duty rate would apply on an across-the-board basis to imports regardless of the COO and, in the case of China only, additional tariffs of 7.5% or 25%. And then everything was suddenly put into motion this year as the whirlwind jumped two or three categories in severity.

2025 TRADE ACTIONS AIMED ON A COUNTRY-SPECIFIC BASIS

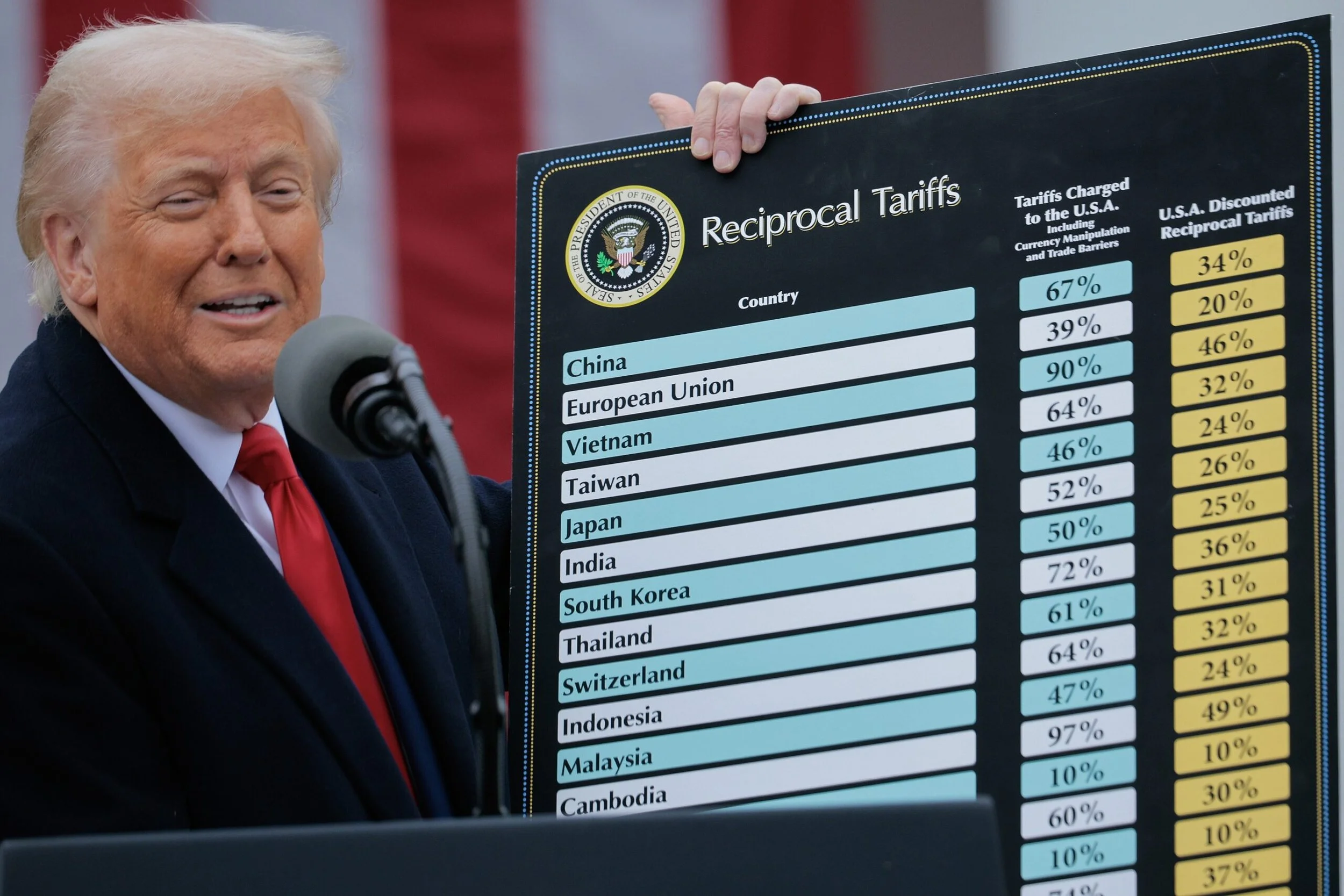

The various “reciprocal” tariffs were at country-specific rates. As a result of the COO dictating the duty rate, COO took center stage. This is most evident in the case of China. At one point, the tariff levels for our vertical turret lathe with a COO of China were as follows:

Normal duty 4.2% + Section 301 25.0% + IEEPA tariff 20.0% + Reciprocal tariff 125.0% = Total 174.2%

At the time of this writing, new “trade deals” between the U.S. and its trade partners are in progress. There are bilateral agreements with the UK and Vietnam and others are under negotiation. Apart from the fact that some in the Senate are demanding that any such trade deals require Congressional approval, there is always the possibility that these may be revised. Let’s correct that—it is probable that trade deals may be revised.

The most important point is that the duty rates may well vary from one country to another. That absence of uniform rates is a radical departure from the heretofore stable program of a standard Column 1 duty rate applying to almost all imports regardless of COO. The duty rates fixed by these bilateral agreements are applied on an across-theboard basis, e.g., 20% on imports from Vietnam. The implication: not much is to be gained by tariff classification strategies. This new approach with the COO’s role as a duty rate-setter accentuates its importance.

Apart from the reciprocal tariffs, another arena where COO plays an important role is the de minimis shipment program. The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA) eliminates the de minimis program for all commercial shipments as of July 1, 2027. Until then, importers can take advantage of the Section 321 de minimis program. This allows goods valued at less than $800 on a given day into the U.S. market free of all formalities and free of duty. In the case of China, however, the Trump IEEPA measure had already eliminated Chinese goods from Section 321 participation as of June 2, 2025. That “loophole” had allowed Chinese products to dodge the Section 301 China tariffs as well as normal tariffs. All of this means that there is an incentive to ensure a COO other than China, at least while this Section 321 window remains open for commercial shipments.

In the first six months of 2025, there were over 500 rulings issued by CBP on COO questions. That is a sign of the continued, in fact increased, importance attached to COO. Beyond the impact on duty rates, it is vital to understand the potential compliance repercussions attached to customs violations, necessarily including false COO claims. The Justice Department announced a new initiative on customs issues to be addressed by False Claims Act filings and also civil actions and criminal prosecutions by its Market Integrity and Major Frauds (MIMF) Unit. This raises the stakes on COO declarations.

All of this has led us to the question: How is the COO determined?

RULES TO DETERMINE COO

The very first point to make is that the plural is the correct form—there is no single rule to determine country of origin. Instead, we have a gaggle of rules, with two major divisions between preferential (free trade agreements, Generalized System of Preferences (GSP)) and non-preferential (duty rate assignment, COO marking). Beyond that, we have rules playing a role in trade remedies, where the rules are read with a bias toward including articles within the scope of an AD or CVD Order, and in government procurement, so as to determine eligibility for treatment under the Trade Agreements Act of 1979 for Buy American Act preferences.

The preferential rules of origin are more precise and objective, the eligibility based on substantial transformation tests that are typically spelled out in specific tariff classification shifts or on precisely calculated regional value content, based upon Bill of Materials analyses. If the Generalized System of Preferences is ever reinstated, the 35% value content and the dual substantial transformation tests will be applied. They are grounded in more objective standards.

WTO AGREEMENT ON RULES OF ORIGIN

The second point is that, for COO purposes, there is no agreed single authoritative source such as the Harmonized Tariff System or the WTO’s Customs Valuation Agreement. The WTO Agreement on Rules of Origin3 is not in the same league. The nearest thing that can be said to be a standard is found in Article 1.1, where we find that rules of origin are defined as those laws, regulations and administrative determinations of each Member. The references in Art. 1.2 to other WTO Agreements add nothing. In other words, there is no rule of origin established other than that in force in each country. The provisions in Art. 5 for promulgating new or modified rules do nothing to fill this void. Finally, as is the case with classification and valuation, there is a provision for a WCO Technical Committee (Art. 4.2 and Annex I), but that Committee has not been able to accomplish as much as its sister technical committees at the WCO. That is not entirely a surprise as it would not have much to work with.

On the other hand, the work programme [sic] for the Committee is based on the aspirational Part IV of the Agreement, Harmonization of Rules of Origin. It is there that we find some substantive contours for the rules of origin. While there is no defined, prescriptive rule at present or in the future, the shared characteristics of the individual countries’ rules of origin should be harmonized around the following concepts:

-

A single non-preferential ROO for all non-preferential purposes;

-

COO should be based on the country where the product has been wholly obtained (this is for manufactured goods where all parts and production are locally derived) or the country where the last substantial transformation was carried out;

-

ROO should be objective, understandable and predictable;

-

Notwithstanding the measure or instrument to which they may be linked, ROOs should not be used as instruments to pursue trade objectives directly or indirectly. They should not themselves create restrictive, distorting or disruptive effects on international trade;

-

ROOs should be administrable in a consistent, uniform, impartial and reasonable manner;

-

ROOs should be coherent;

-

ROOs should be based on a positive standard.

The notion of “substantial transformation” has just made its appearance. This principle will play a prominent role in the remainder of this discussion. But we should first stay with the WTO Agreement for a moment. Is there a definition of substantial transformation? No, but the Agreement calls upon the Committee to elaborate on the notion of changes in tariff classification as the basis for establishing that a transformation can qualify as “substantial.” We should recognize that this “tariff shift” rule is a normal eligibility criterion for the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and other free trade agreements (FTAs). The Agreement implicitly posits the tariff shift rule as the basis for a working definition of substantial transformation, as it proceeds to note that, “when the exclusive use of the HS nomenclature does not allow for the expression of substantial transformation,” exceptionally ad valorem percentages—value add (think Regional Value Calculation in an FTA context)—and/or specific manufacturing or processing operations might be considered. The tariff shift rule and the value-add rule have the significant advantage that each of them is based on an objective criterion, one easily ascertained and measured. Whether or not a transformation is “substantial” as a valid COO test suffers by comparison.

We will engage in a comprehensive review of the U.S. views on the substantial transformation rule. Before doing so, we should take note of the Revised Kyoto Convention.

REVISED KYOTO CONVENTION (RKC)

Formally the Convention on the Simplification and Harmonization of Customs Procedures, the Kyoto Convention was first released by the predecessor of the WCO in 1974. It was revised in 1999 with effect from 20064 . Its title is self-explanatory and its ultimate goal is to encourage international trade. The RKC should be seen as a useful adjunct to the WTO and WCO trade facilitation efforts, best embodied in the Trade Facilitation Agreement of 20145 . The RKC is organized into a General Annex of ten chapters and then ten specific annexes that address the procedures for specific events, e.g., arrival of goods, importation and exportation, or special procedures for such subjects as travelers or offences [sic]. Of relevance here is Annex K, Origin, where we find the definition in its Chapter 1:

“substantial transformation criterion” means the criterion according to which origin is determined by regarding as the country of origin the country in which the last substantial manufacturing or processing, deemed sufficient to give the commodity its essential character, has been carried out.

This introduction of an “essential character” benchmark was followed by Recommended Practices including, inter alia, the following:

-

Recommended Practice

Where two or more countries have taken part in the production of the goods, the origin of the goods should be determined according to the substantial transformation criterion. -

Recommended Practice

In applying the substantial transformation criterion, use should be made of the International Convention on the Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding System. -

Recommended Practice

Where the substantial transformation criterion is expressed in terms of the ad valorem percentage rule, the values to be taken into consideration should be:-

For the materials imported, the dutiable value at importation or, in the case of materials of undetermined origin, the first ascertainable price paid for them in the territory of the country in which manufacture took place; and

-

For the goods produced, either the ex-works price or the price at exportation, according to the provisions of national legislation. You see references here to the tariff shift rule and to a value-add rule. Again, either of these tests would deliver objectivity to the COO review. Humming along with this international tafelmusik, we have arrived at the U.S. practices on determining COO.

-

CURRENT U.S. VIEWS ON COO

The standard exploration of COO might begin at the beginning, which is the definition. From Section 134.1(b) of the customs regulations6 , we learn that “country of origin” means: the country of manufacture, production, or growth of any article of foreign origin entering the U.S. Further work or material added to an article in another country must effect a substantial transformation in order to render such other country the “country of origin” within this part; for a good of a NAFTA or USMCA country, the marking rules set forth in part 102 of this chapter (hereinafter referred to as the part 102 Rules) will determine the country of origin. Enter the notion of substantial transformation. We must observe that the part 102 Rules are actually comprised of two subparts. The first consists of Sections 102.11-102.20 and is more commonly known as the “NAFTA marking rules.” The second deals with the rules governing the COO of textile and apparel products and, not surprisingly, are often referred to as the “textile marking rules” (Section 102.21). These rules, with their very narrow application, have the sought-after objective standards so lacking in the general COO rules. They are based on tariff shift measures and, in some instances, in the textile/apparel rules, impose specific means of production. As a direct result of the precision of these part 102 Rules, there are relatively few challenges in their application.

Not so with the generally applicable rules. Here we must note that the customs regulations at Sections 134.1-.55 govern the marking of imported articles. They implement the statute, Section 304 of the Tariff Act of 19307 , which mandates that:

every article of foreign origin (or its container…) imported into the United States shall be marked in a conspicuous place as legibly, indelibly, and permanently as the nature of the article (or container) will permit in such manner as to indicate to an ultimate purchaser in the United States the English name of the country of origin of the article.

One would expect that the rules for determining the COO for marking purposes and the COO for normal, i.e., nonpreferential, duty rate purposes and the COO for preferential duty purposes and the COO for trade remedy liability should be one and the same. But they are not at all the same or even aligned. Recalling that the shared purpose of the rules is to objectively define a COO test, how is it possible that an imported article can merit an exemption from normal tariffs by meeting the USMCA eligibility rule—but at the same time be subject to additional Section 301 China tariffs8 ? This is not the forum to explore in depth the disconnect in the U.S. COO regime for trade remedy purposes vs. nonpreferential duty vs. tariff preferences. This is a good point to recall the WTO Agreement texts:

- Notwithstanding the measure or instrument to which they may be linked, ROOs should not be used as instruments to pursue trade objectives directly or indirectly. They should not themselves create restrictive, distorting or disruptive effects on international trade;

- ROOs should be administrable in a consistent, uniform, impartial and reasonable manner.

The U.S. government’s longstanding practice of applying a separate and distinct gloss on COO rules to effectuate a specific trade policy9 makes a jest of that second bullet point. To be clear, the EU’s ploy of inserting an “economically justified” overlay on origin is an even more egregious departure from these principles10 . The Trump Administration introduced a similar subjective gloss on origin in its bilateral tariff agreements. We find that a standard duty rate of, say, 15% will be assessed on products of the bilateral trade partner, but a 40% rate will be reserved for goods that will be “transshipment.” There has been no official, broadly defined definition of that term, but the July 31 Executive Order on Further Modifying the Reciprocal Tariff Rates11 warns us:

Sec. 3. Transshipment. (a) An article determined by CBP to have been transshipped to evade applicable duties under section 2 of this order shall be subject to (i) an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 40 percent, in lieu of the additional ad valorem rate of duty applicable under section 2 of this order to goods of the country of origin, (ii) any other applicable or appropriate fine or penalty, including those assessed under 19 U.S.C. 1592, and (iii) any other United States duties, fees, taxes, exactions, or charges applicable to goods of the country of origin. CBP shall not allow, consistent with applicable law, for mitigation or remission of the penalties assessed on imports found to be transshipped to evade applicable duties.

A July 31, 2025 CBP message to the trade community12 on the Canadian Reciprocal Tariff program gives us the tariff provision detail:

For goods that are determined by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to have been transshipped to evade the additional ad valorem for products of Canada, CBP will direct the importer that such goods are subject to the following HTSUS classification and additional duty rate:

9903.01.16: Except for [certain] products …, articles the product of Canada that are determined by CBP to have been transshipped to evade applicable duties, will be assessed an additional ad valorem rate of duty of 40%

So, in spite of the fact that any and all substantial transformation rules might have been applied and met, if CBP perceives the purpose was to evade the duties, then the imported article will be seen as having retained its original COO status and a higher tariff, viz. 40% vs. 35% in the case of Canada, will be assessed. The importer also faces a penalty investigation.

This plan, sure to be challenged in its application, is in complete alignment with the EU views of an “economic justification” in its disregard for commercial practices and its jettison of normative standards to effect a desired policy outcome. Both schemes are troublesome.

Let us proceed to a review of the COO tests employed by CBP.

COO TESTS IN PLAY

The background to this discussion is founded on two facts: (1) there have been thousands of COO rulings issued by CBP in the past several years alone, and (2) those rulings have been issued by CBP Headquarters and by individual National Import Specialists. The result of so many authors is that there is no single standard to be discerned despite the fact that many rulings pay overt obeisance to the traditional “name, character, or use” test or pledge a review of the totality of circumstances. An informal review of even a small sampling of these COO rulings will yield a surprising range of analytical rubrics.

The Name, Character, or Use test

The test traditionally applied by the U.S. to determine whether a substantial transformation has occurred is expressed by the following: “ A substantial transformation is said to have occurred when an article emerges from a manufacturing process with a name, character, or use which differs from the original material subjected to the process.”13 This is the oft-quoted and venerable “name, character, or use” test. Exactly how to apply this test has been subject to a variety of standards and suggested standards. CBP has cautioned14 that:

In addition to the name, character, and use criteria, courts have also considered subsidiary or additional factors, such as the country of origin of the item’s components, the extent and nature of operations performed, value added during processing, a change from producer to consumer goods, or a shift in tariff provisions… Consideration of subsidiary or additional factors is not consistent, and there is no uniform or exhaustive list of acceptable factors.

The variegated nature of these standards will be revealed.

Nature of the Manufacturing/Assembly Process

A substantial transformation will not result from a minor manufacturing or combining process that leaves the identity of the article intact.15 The Cyber Power16 decision re-affirmed the longstanding “minor vs. substantial” or “simple vs. complex” assembly review, observing the subjective nature of the test: “Without objective standards, such as cost, or a working definition of ‘simple assembly,’ the court is left to arbitrarily apply its own subjective standards. Without workable, objective standards, one court’s ‘mere assembly’… can just as easily be another court’s complex process.” The court observed that there was an objective standard set in the customs regulations, with the definition of a “simple assembly”:

Simple assembly. “Simple assembly” means the fitting together of five or fewer parts all of which are foreign (excluding fasteners such as screws, bolts, etc.) by bolting, gluing, soldering, sewing or by other means without more than minor processing.17 As one will expect, the review of the assembly/production process will need to be conducted on the basis of the specific details presented in each case. It is essential that the factors to be taken into consideration in judging the assembly process will (or at least should) include, without limitation:

-

the number of workers involved;

-

the level of workers’ skill required;

-

specialized training of the workers;

-

the nature and relative costs of the equipment required;

-

the number of discrete stages and steps required for production;

-

the time required for the assembly;

-

the nature (physical processes) of the assembly or production;

-

the relative processing costs; and

-

the value added by the assembly.

The supporting information would be provided with full documentation: commercial documents (POs, invoices, etc.) and customs documents for the imported parts and components, certificates of origin, Bills of Materials, as well as flowcharts, narrative descriptions, still photographs or videos depicting the assembly process, as well as the capabilities of the manufacturing facility.

In a recent 2025 ruling18 , we see that CBP may first inquire into the nature of the assembly, implying that only if it is not significant will the agency make further analyses:

Regarding the country of origin of the replacement RO water filters, it is our opinion that the assembly process performed in China is not complex and does not constitute a substantial transformation. The process predominantly involves gluing, welding, and pressing various components into place. The combining of these parts in China does not create a new and different article of commerce with a name, character, and use distinct from the individual components. Therefore, to determine the country of origin of the replacement RO water filters, we rely on the origin of the RO membrane filter, which provides the essential function of the filters. It is the RO membrane filter from South Korea which requires considerable technical expertise and customized equipment to produce. It is also the most expensive portion of the filters and is the item performing the filtering of the water.

Given the primacy of this issue, importers heeding this advice should resolve to carefully curate and present the full panoply of supporting documentation. It would be a mistake to skim over this process. The fact that CBP has made the following admission19 must be borne in mind:

CBP has never outlined a bright line rule in which the number of manufacturing steps or time taken in a country would render an article substantially transformed. See, e.g., HQ H317645, dated October 5, 2021 (“a review of each ruling reveals that the outcomes do not rely simply on the number of components, the number of assembly steps, the time it takes to complete assembly, or the number of workers.”)

In short, there is no such thing as overkill here.

ORIGIN OF THE COMPONENTS WHICH CONFER THE ESSENCE OR ESSENTIAL CHARACTER

In the CBP rulings, we find references variously to main components20 , core components21 , critical components22 or key components23 . We can travel back to the Ferrostaal decision in 198724 when the Government had argued that the name, character, or use test had been displaced by an “essence” test. The court made clear that the traditional test was at the heart of the authorities cited for this proposition and that the traditional test remained valid. In a 2025 ruling on the COO of gokarts25 , we find an application of this test:

While CBP has not yet ruled on the country of origin of a go-kart, you claim that CBP has previously ruled that the frame of “similar” vehicles, such as All-Terrain Vehicles (“ATVs”), electric bikes, and motorcycles imparts the riding apparatus’s essential character. It is our opinion that these go-karts are not akin to those types of vehicles. It is the opinion of this office that, since the bulk of the go-karts is sourced from China, and the frame, while significant, does not impart the same level of importance, the country-of-origin of models GK200 and EVGK200 is China.

In the same vein we might cite to another 2025 ruling where, after stating that the assembly operation was not a complex process, we find the following CBP explanation in its analysis of the COO of an imported sunroof:

You describe this process as a technology that makes the glass an integrated frame, allowing it to be easily attached to the body without adhesives or clips. However, the glass itself does not undergo any change, and the integrity of the glass remains the same. The processes performed in South Korea do not transform the glass into a new article, as the enduse of the glass is predetermined. Since the glass is the main component of the sunroof assembly and the rest of the components are ancillary, the country of origin of the sunroof assembly will be the country of origin of the glass. Underline added.

CBP may take into account the individual costs or values represented by the components on the Bill of Materials as a factor in assigning “key component” status26 . Closer analysis may reveal that the CBP review’s purpose may be to discern whether there were any changes made to the component which provides the essence of finished product. As an example, in the case of imported battery modules and battery packs, CBP looked to the key components (battery cells) and determined27 that:

The assembly operations in Canada do not change the battery cells, which provide the essence of the battery module and subsequent battery pack, into an article with a new name, character, or use, different from that possessed by the article prior to processing. The function of the battery cells is to store and provide power, and the function of the battery cells in the battery modules and battery packs is likewise to store and provide power. In view of these facts, the country of origin of the subject battery module…and the battery pack… for the purposes of Section 301 is China, Japan, or Korea, dependent upon where the battery cells are manufactured.

What might the CIT say? Again, we may cite to Cyber Power, where the court declared that:

The court reiterates its prior rejection of two potential alternatives to the substantial transformation test of name, character, or use: first, an “essence”-based approach that would look only to whether the essential or critical component of a product had been transformed; and second, an approach that would per se decide whether substantial transformation had occurred on a component-by-component basis.

The court was unequivocal in its support for a totality of circumstances test, as discussed below. Nevertheless, we find many component-centric rulings.

PREDETERMINED END USE OF THE COMPONENTS

While this standard is most associated with the 2016 decision in Energizer Battery28 , a government procurement case that has been widely invoked by CBP for COO cases more generally, we can trace its origins back to 1987 CIT decision, Superior Wire v. United States, even though the formulaic phrase is absent29 . The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit then affirmed the CIT’s determination that the cold-drawing of wire rod into wire was a minor operation which did not result in a substantial transformation, downplaying the fact that the physical properties of the wire rod, and therefore its use, were affected as a result of the processing (“such changes appear to be primarily cosmetic in the light of the predetermined qualities and specifications of the wire rod”)30 .

The record in that case showed that the wire that emerged from the drawing process was stronger and rounder than the wire rod. However, because these properties of the wire, which affected the use to which it could be put, were predetermined by the chemical content of the rod and the cooling process used in its manufacture, the court found that wire drawn from the rod was not a new and different product, but rather the last stage in the processing of the same product. Cf. United States v. Kanthal, 554 F.2d 456, 64 CCPA 89 (1977) on the notion that drawing steel rod through a die marks a point of significant product transformation, i.e., creates a “finished product” (wire) from a steel “mill product” (rod)31 . Superior Wire obliterated this distinction.

I find that the Superior Wire analysis can lead to absurd results. For example, why should the predetermined use logic train stop at the wire rod station? If the chemicals present in the wire rod speak to the ultimate properties of the wire and thus speak to a predetermined use, those chemicals would have been introduced into the alloy at the blast furnace. The application of a “pre-determination” principle would lead to the conclusion that none of the production steps from the pouring of the molten steel forward would mark a change in use and character: first, the making of the billet: melting raw materials (like scrap steel or iron ore) in a furnace, then casting the molten steel into a mold or using a continuous casting machine. The solidified billet, often with a square or rectangular cross-section, is then cooled, straightened, and cut to the desired length. Production of the wire rod follows: in a hot roll process, blooms or billets are heated and then rolled to the required diameter through a series of rolling passes (generally referred to as roughing, intermediate and finishing passes). Would these production steps also be dismissed?

The CIT addressed this concept of predetermined end use in the 2022 decision in Cyber Power32 . The court rejected the notion of a predetermined end use as a determinative factor (“…a consideration [of intended use] is but one of many for the court to consider as part of the “totality of the evidence”). Apparently, the Government had argued that predetermined end use would preclude a finding of substantial transformation:

If, as Defendant argues, components assembled for a predetermined use may never constitute substantial transformation, then, for all practical purposes, there can never be a substantial transformation because there will always be a predetermined use… It is one thing to say that the attachment of a handle to a pan, or a sole to a shoe, is too mundane for a substantial transformation; it is another to suggest that all parts (however many) assembled into a “predetermined” product may never result in a substantial transformation. That is not, and cannot be, the law. Underline added33.

CBP has continued to apply the predetermined use rule with vigor. See, e.g., Ruling Nos. N344905 (1/15/25) (In this condition, the casting is recognizable as a sprocket that will transmit power. It has a predetermined end use prior to being subject to the described finishing processes in China. As such, the processes completed in China do not substantially transform the sprocket casting, nor do they change the shape, character, or predetermined use of the Vietnamese casting.); N348532 (5/27/25) (CBP refers to a predetermined use conferred by a casting in a foreign country); N348185 (5/15/25) (CBP first invoked the totality of the evidence standard before going into a predetermined end use approach, coupled with a main component vs. ancillary component comparison); H343750 (6/4/25) (Just like the hand tool components in Nat’l Hand Tool Corp., the components of the barrel saunas have a predetermined use and their character and use remain unchanged after they are packaged in Mexico. In addition, the continuous shaping of the wooden staves and packaging occurring in Mexico is a relatively simple combining operation that does not change the name, character, or use of the individual Chinese-origin components).

Rather than taking the view that Cyber Power court simply eliminated the predetermined use test altogether, CBP has countered that the Cyber Power court did not reject or call into question the predetermined use test, but rather cautioned that the standard is but one of many factors to be considered in a substantial transformation analysis. Ruling no. H327993 (11/10/22). But that is disingenuous. If the predetermined use test is applied, then the importer has already lost on the “use” leg of the test and is left to show a change in name or character.

In any event, I think the definition of “use” in these circumstances is too narrow. Taking the example of the wire rod in Superior Wire, from the very point of mixing in the carbon or manganese in the steel mill, the specific use of the wire rod or, indeed, the steel wire, can be said to have been predetermined. I think the better approach is to ask whether the imported article was already fit or suitable for that use at the time that the article or the materials or parts used to make that imported article were imported into the intermediate country. That criterion of “capability of use” seems better suited to the task of ascertaining substantial transformation. On one level, the intended use of all or almost all components as parts to be assembled or further manufactured in the production of the finished article will have been predetermined. All or almost all may have been imported into that intermediate country for that purpose and for no other. The better question is whether the processing in that intermediate country will have rendered the finished product capable of that intended use.

If we carefully scrutinize the 2023 Cyber Power decision, we find it is aligned with this interpretation, with Judge Gordon observing34 for one product that:

…Philippine manufacture satisfies all three prongs of the substantial transformation test: a change in name (from a set of …component parts to the finished, functioning UPS…), a change in character (from component parts not yet capable of being electronically programmed to a device capable of performing a number of intelligent functions), and a change in use (from component parts to a device geared towards a specifically identified purpose: protecting against power outages).

You will see that the criterion of capability of use is actually classified in this quoted text as a change in character, rather than a change in use. The court also noted a distinct change in use itself. It makes no difference in the outcome, as the test is disjunctive—the test is satisfied if any one of the three legs has been met35 . Here, the court found all three criteria were met. In any event, the predetermined use test should be scrapped.

We will find a consistency of analysis in another CIT decision from 2000. In the Sassy case36 , we find the remarks concluding the court’s review:

…Further, the court concludes as a matter of law that the article emerging [a baby’s pacifier] has a different name, character and use than the original material. All of the witnesses who testified named each of the component parts as nipples, teats or baglets, a shield, a knob, and a retaining plug. The witnesses likewise testified that the finished article was a pacifier. Thus, a change in name clearly occurs. A change in character also occurs. Character is “one of the essentials of form, structure, materials, or function that together make up and usu[ally] distinguish the individual”… While the component parts are readily identified in the pacifier, the function of the finished good is different from the component part. Further, once welding occurs, the component parts cannot be disassembled without destroying the finished goods. Finally, a change in the use of the materials occurs. Before the component materials are assembled in Hungary, each piece is without any use beyond manufacture into a pacifier. Once the operations are completed in Hungary, the pacifier may be used by infants for its intended purpose. [Citation omitted; Underline added]

We might take the simple example of 3,500 discrete parts imported into a country to assemble an automobile. Each of the 3,500 parts shares the same predetermined (or “intended”) use, and the identity of each of the parts remains unchanged. Leaving aside the obvious nature of the assembly (simple vs. complex) is there anyone who would argue as a matter of law that there has not been a change in the use of the standalone part, e.g., a camshaft, since it is now subsumed in the automobile and that finished product has a separate use? Who would argue that each leg of the name, character, or use tripod has not been satisfied, as in that one product in Cyber Power?37 We are left with many CBP rulings which show us that CBP has not got the message38 I suspect we await another court challenge. If the Government were to lose many will wager that they will not file an appeal lest they are confronted with an adverse court decision at the appellate level.

CHANGE IN TARIFF CLASSIFICATION

Even in the context of the name, character, or use test, and thus in the absence of a tariff shift test, the customs courts have considered a change of tariff classification as a measure of substantial transformation39 . There is no reason why a ruling or a protest might not cite to a tariff shift as an additional factor.

TOTALITY OF EVIDENCE

As we have seen, the court in Energizer Battery cited to National Hand Tool for the notion of a predetermined use. But in National Hand Tool, the trial court held that “[t]he fact there was only predetermined use of the imported article” would not necessarily preclude a finding of a substantial transformation. That court directed that the inquiry must go further—the determination of substantial evidence must be based on the totality of the evidence40 .

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

After a review of the foregoing you should have taken on board the following:

-

The assignment of different duty rates on a COO basis will continue to drive relocations of production with the hope of attaining lower duty rates through a change in COO.

-

The foreign suppliers may seek to shift as little of the process as is necessary to attain the desired COO shift.

-

To this point there is not yet a single ROO in force and effect at the international level, unlike tariff classification and customs valuation—the best that is hoped for is a harmonization of the individual ROOs.

-

The applicable COO rules of origin in any given import transaction will be those articulated by the country of importation.

-

In the U.S., the ROOs are based on the commonly accepted notion of substantial transformation.

-

Substantial transformation, in turn, is defined as having a change in the name, character, or use of the components of products.

-

There is a lack of uniformity in CBP’s employing various standards to evaluate and apply the name, character, or use test.

-

The private sector and CBP may apply different standards in their respective planning and review analyses.

-

CBP will closely examine the facts surrounding the production of the imported products.

-

Importers are left to soldier on as they step gingerly through this befuddling terrain.

-

Prudence dictates that an importer will be best served if it can meet all the standards that might be applied, but most especially if the importer will be able to prove that the assembly/ production process is substantial and complex and not minor and simple.

End Notes

This article was originally published in the Journal of International Taxation in the September/October 2025 edition

Any content provided by our bloggers, contributors, or users is their opinion, and they are responsible for the accuracy, completeness, and validity of their statements. Trade Duty Refund does not guarantee the accuracy or reliability of any opinions expressed in the content.

-

This is the case for ad valorem duties. We leave aside specific tariffs, such as a tariff based on weight or dimensions. ↩

-

The very day after this last sentence was drafted, the Wall Street Journal carried the article: Emont, U.S. Tariffs Prompt China Manufacturers to Pivot to Vietnam, Wall. St. J., Jul. 14, 2025, at 1, col. 5. The article reported that there have been 800 new investment projects in Vietnam from China and Hong Kong this year. ↩

-

The text is available online at https://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/ ro_e.htm ↩

-

The text is available online at https://www.wcoomd.org/en/Topics/Facilitation/ Instrument%20and%20Tools/Conventions/ pf_revised_kyoto_conv/Kyoto_New ↩

-

Formally the Agreement on Trade Facilitation. The text is available at https://www.wto.org/ english/docs_e/legal_e/tfa_e.htm ↩

-

19 CFR § 134.1(b). ↩

-

Codified at 19 U.S.C. § 1304. ↩

-

See, e.g., Ruling No. H343750 (6/4/25) ↩

-

See Ferrostaal Metals Corp. v. United States, 11 CIT 470, 664 F. Supp. 535 (1987). See also Cyber Power Systems (USA) Inc. v United States, 560 F.Supp.3d 1347 (CIT 2022). ↩

-

Union Customs Code Art. 60(2). See Neville, “It ain’t what you do, but why you do it…European Origin Decision Stretches the Boundaries of Origin Determinations,” 34 JOIT July 2023 at 20. ↩

-

Published at 90 Fed. Reg. 14326 (Aug. 6, 2025) ↩

-

CSMS 65798609 (7/31/25) ↩

-

United States v. Gibson-Thomsen Co., Inc., 27 CCPA 267, C.A.D. 98 (1940); Texas Instruments v. United States, 681 F.2d 778, 782 (CCPA 1982). ↩

-

Ruling No. H335829 (2/26/25). ↩

-

See National Hand Tool Corp. v. United States, 16 CIT 308 (1992), aff’d, 989 F.2d 1201 (Fed. Cir. 1993). ↩

-

Cyber Power Systems (USA) Inc. v United States, 560 F.Supp.3d 1347 (CIT 2022). ↩

-

19 CFR 102.1(p). The term “minor processing” is defined as well. 19 § CFR 102.1(n). ↩

-

Ruling No. N349316 (6/5/25). ↩

-

Ruling No. H335829. ↩

-

See Ruling No. N341088 (7/16/24) ↩

-

See Ruling No. H346297 (CBP has held that whether an assembly process is sufficiently complex to rise to the level of a substantial transformation is determined upon consideration of all the operations that occur within that country. Based upon your description of the manufacturing operations, the operational steps do not appear particularly complex. They consist of assembling a Chinese gearbox and other accompanying components with the core subassemblies (i.e., electric motor assembly and drum assembly) that are produced entirely in Thailand. Thus, based on the totality of the circumstances, the country of origin of the electric winch…will be Thailand.) ↩

-

See, e.g., Ruling No. N338577 (3/30/24). ↩

-

See, e.g., Ruling No. N339983 (5/29/24) ↩

-

See 11 CIT at 473-474. ↩

-

Ruling No. N349255 (6/12/25). ↩

-

See Ruling No. N333554 (7/10/23). ↩

-

Ruling No. N329847 (1/10/23). See also Ruling Nos. N333554 (7/10/23) and H339955 (9/6/24) ↩

-

Energizer Battery, Inc. v. United States, 190 F. Supp. 3d 1308 (2016). This decision cited to: (1) National Hand Tool Corp. v. United States, 16 CIT 308 (1992), aff’d per curiam, 989 F.2d 1201 (Fed. Cir. 1993), where the court determined that components (flex sockets, speeder handles, and flex handles) used to make hand tools were not substantially transformed within the United States because, inter alia, the intended use of the articles was predetermined at the time of importation), and (2) Uniroyal, Inc. v. United States, 3 CIT 220, 542 F. Supp. 1026 (1982). I criticized the Energizer Battery decision in Neville, “CBP’s Hammer: Misuse of Energizer Battery,” 30 JOIT Nov. 2019 at 30 ↩

-

11 CIT 608, 669 F. Supp. 472 (CIT 1987), aff’d, 867 F.2d 1409, 7 Fed. Cir. 43 (Fed. Cir. 1989). ↩

-

Id., 7 Fed. Cir. at 49. ↩

-

In this connection, see The Torrington Co. United States, 3 Fed. Cir. 158, 167 (1985), where the court noted the difference between steel “producers’ goods” and steel “consumers’ goods” that had been featured in a 1970 Customs Court case. ↩

-

Cyber Power Systems (USA) Inc. v United States, 560 F.Supp.3d 1347 (CIT 2022). In the course of denying cross motions for summary judgment, the court rejected the notion of a pre-determined end use as a determinative factor (“…a consideration [of intended use] is but one of many for the court to consider as part of the ‘totality of the evidence’”). There was a later decision on the merits, Cyber Power Systems (USA) Inc. v United States, 622 F.Supp.3d 1397 (CIT 2023). ↩

-

560 F.Supp.3d at 1355 ↩

-

622 F. Supp. 3d at 1412 ↩

-

The appellate court has noted that only one of the three prongs must be met. United States v. International Paint Co., 35 CCPA 87, C.A.D. 376 (1948), cited in Koru North America v. United States, 12 CIT 1120, 1126 (CIT 1988). ↩

-

Sassy, Inc. v. United States, 24 CIT 700 (2000); see also Uniden Am. Corp. v. United States, 24 CIT 1191, 1195, 120 F. Supp. 2d 1091, 1095 (2000) ↩

-

But see Ruling No, H302821 (7/26/19) (passenger vehicles assembled in Sweden have China COO), which may possibly be distinguished on its facts and it also pre-dates Cyber Power. ↩

-

See especially Ruling No. H322161 (3/14/23) ↩

-

See Ferrostaal, 11 CIT at 478 ↩

-

National Hand Tool, 16 CIT at 312, citing to Ferrostaal, 11 CIT at 478, 664 F. Supp. at 541 and National Juice Products v. United States, 10 CIT 48, 61, 628 F. Supp. 978, 991 (CIT 1986). ↩